Sustainable investment can be radically different from traditional investment. „Asset Allocation, Risk Overlay and Manager Selection“ is the translation of the book-title which I wrote in 2009 together with two former colleagues from FERI in Bad Homburg. Sustainability plays no role in it. My current university lecture on these topics is different.

Sustainability can play a very important role in the allocation to investment segments, manager and fund selection, position selection and also risk management. Strict sustainability can even lead to radical changes: More illiquid investments, lower asset class diversification, significantly higher concentration within investment segments, more active instead of passive mandates and different risk management. Here is why:

Central role of investment philosophy and sustainability definition for sustainable investment

Investors should define their investment philosophy as clearly as possible before they start investing. By investment philosophy, I mean the fundamental convictions of an investor, ideally a comprehensive and coherent system of such convictions (see Das-Soehnholz-ESG-und-SDG-Portfoliobuch 2023, p. 21ff.). Sustainability can be an important element of an investment philosophy.

Example: I pursue a strictly sustainable, rule-based, forecast-free investment philosophy (see e.g. Investment philosophy: Forecast fans should use forecast-free portfolios). To this end, I define comprehensive sustainability rules. I use the Policy for Responsible Investment Scoring Concept (PRISC) tool of the German Association for Asset Management and Financial Analysis (DVFA) for operationalization.

When it comes to sustainable investment, I am particularly interested in the products and services offered by the companies and organizations in which I invest or to which I indirectly provide loans. I use many strict exclusions and, above all, positive criteria. In particular, I want that the revenue or service is as compatible as possible with the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (UN SDG) („SDG revenue alignment“). I also attach great importance to low absolute environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks. However, I only give a relatively low weighting to the opportunities to change investments („investor impact“) (see The Soehnholz ESG and SDG Portfolio Book 2023, p. 141ff). I try to achieve impact primarily through shareholder engagement, i.e. direct sustainability communication with companies.

Other investors, for whom impact and their own opportunities for change are particularly important, often attach great importance to so-called additionality. This means, that the corresponding sustainability improvements only come about through their respective investments. If an investor finances a new solar or wind park, this is considered additional and therefore particularly sustainable. When investing money on stock exchanges, securities are only bought by other investors and no money flows to the issuers of the securities – except in the case of relatively rare new issues. The purchase of listed bonds or shares in solar and wind farm companies is therefore not considered an impact investment by additionality supporters.

Sustainable investment and asset allocation: many more unlisted or alternative investments and more bonds?

In extreme cases, an investment philosophy focused on additionality would mean investing only in illiquid assets. Such an asset allocation would be radically different from today’s typical investments.

Better no additional allocation to illiquid investments?

Regarding additionality, investor and project impact must be distinguished. The financing of a new wind farm is not an additional investment, if other investors would also finance the wind farm on their own. This is not atypical. There is often a so-called capital overhang for infrastructure and private equity investments. This means, that a lot of money has been raised via investment funds and is competing for investments in such projects.

Even if only one fund is prepared to finance a sustainable project, the investment in such a fund would not be additional if other investors are willing to commit enough money to this fund to finance all planned investments. It is not only funds from renowned providers that often have more potential subscriptions from potential investors than they are willing to accept. Investments in such funds cannot necessarily be regarded as additional. On the other hand, there is clear additionality for investments that no one else wants to make. However, whether such investments will generate attractive performance is questionable.

Illiquid investments are also far from suitable for all investors, as they usually require relatively high minimum investments. In addition, illiquid investments are usually only invested gradually, and liquidity must be held for uncertain capital calls in terms of timing and amount. In addition, illiquid investments are usually considerably more expensive than comparable liquid investments. Overall, illiquid investments therefore have hardly any higher return potential than liquid investments. On the other hand, mainly due to the methods of their infrequent valuations, they typically exhibit low fluctuations. However, they are sometimes highly risky due to their high minimum investments and, above all, illiquidity.

In addition, illiquid investments lack an important so-called impact channel, namely individual divestment opportunities. While liquid investments can be sold at any time if sustainability requirements are no longer met, illiquid investments sometimes have to remain invested for a very long time. Divestment options are very important to me: I have sold around half of my securities in recent years because their sustainability has deteriorated (see: Divestments: 49 bei 30 Aktien meines Artikel 9 Fonds).

Sustainability advantages for (corporate) bonds over equities?

Liquid investment segments can differ, too, in terms of impact opportunities. Voting rights can be exercised for shares, but not for bonds and other investment segments. However, shareholder meetings at which voting is possible rarely take place. In addition, comprehensive sustainability changes are rarely put to the vote. If they are, they are usually rejected (see 2023 Proxy Season Review – Minerva).

I am convinced that engagement in the narrower sense can be more effective than exercising voting rights. And direct discussions with companies and organizations to make them more sustainable are also possible for bond buyers.

Irrespective of the question of liquidity or stock market listing, sustainable investors may prefer loans to equity because loans can be granted specifically for social and ecological projects. In addition, payouts can be made dependent on the achievement of sustainable milestones. However, the latter can also be done with private equity investments, but not with listed equity investments. However, if ecological and social projects would also be carried out without these loans and only replace traditional loans, the potential sustainability advantage of loans over equity is put into perspective.

Loans are usually granted with specific repayment periods. Short-term loans have the advantage that it is possible to decide more often whether to repeat loans than with long-term loans, provided they cannot be repaid early. This means that it is usually easier to exit a loan that is recognized as not sustainable enough than a private equity investment. This is a sustainability advantage. In addition, smaller borrowers and companies can probably be influenced more sustainably, so that government bonds, for example, have less sustainability potential than corporate loans, especially when it comes to relatively small companies.

With regard to real estate, one could assume that loans or equity for often urgently needed residential or social real estate can be considered more sustainable than for commercial real estate. The same applies to social infrastructure compared to some other infrastructure segments. On the other hand, some market observers criticize the so-called financialization of residential real estate, for example, and advocate public rather than private investments (see e.g. Neue Studie von Finanzwende Recherche: Rendite mit der Miete). Even social loans such as microfinance in the original sense are criticized, at least when commercial (interest) interests become too strong and private debt increases too much.

While renewable raw materials can be sustainable, non-industrially used precious metals are usually considered unsustainable due to the mining conditions. Crypto investments are usually considered unsustainable due to their lack of substance and high energy consumption.

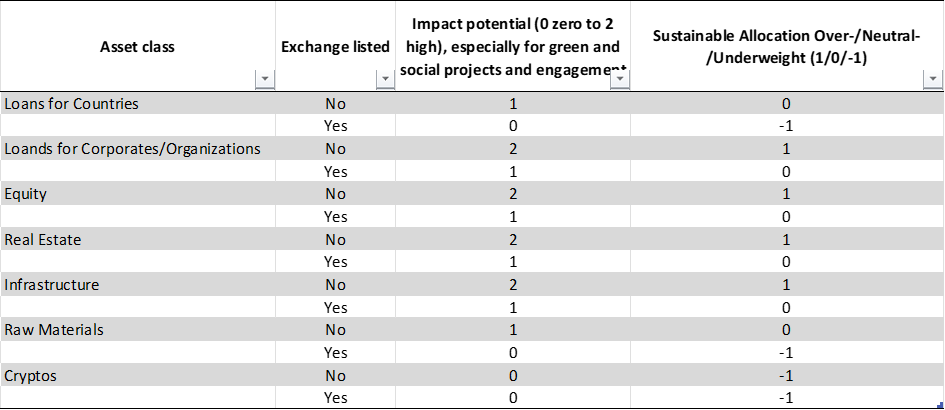

Assuming potential additionality for illiquid investments and an impact primarily via investments with an ecological or social focus, the following simplified assessment of the investment segment can be made from a sustainability perspective:

Sustainable investment: Potential weighting of investment segments assuming additionality for illiquid investments:

Source: Soehnholz ESG GmbH 2023

Investors should create their own such classification, as this is crucial for their respective sustainable asset allocation.

Taking into account minimum capital investment and costs as well as divestment and engagement opportunities, I only invest in listed investments, for example. However, in the case of multi-billion assets with direct sustainability influence on investments, I would consider additional illiquid investments.

Sustainable investment and manager/fund selection: more active investments again?

Scientific research shows that active portfolio management usually generates lower returns and often higher risks than passive investments. With very low-cost ETFs, you can invest in thousands of securities. It is therefore no wonder that so-called passive investments have become increasingly popular in recent years.

Diversification is often seen as the only „free lunch“ in investing. But diversification often has no significant impact on returns or risks: With more than 20 to 30 securities from different countries and sectors, no better returns and hardly any lower risks can be expected than with hundreds of securities. In other words, the marginal benefit of additional diversification decreases very quickly.

But if you start with the most sustainable 10 to 20 securities and diversify further, the average sustainability can fall considerably. This means that strictly sustainable investment portfolios should be concentrated rather than diversified. Concentration also has the advantage of making voting and other forms of engagement easier and cheaper. Divestment threats can also be more effective if a lot of investor money is invested in just a few securities.

Sustainability policies can vary widely. This can be seen, among other things, in the many possible exclusions from potential investments. For example, animal testing can be divided into legally required, medically necessary, cosmetic and others. Some investors want to consistently exclude all animal testing. Others want to continue investing in pharmaceutical companies and may therefore only exclude „other“ animal testing. And investors who want to promote the transition from less sustainable companies, for example in the oil industry, to more sustainability will explicitly invest in oil companies (see ESG Transition Bullshit?).

Indices often contain a large number of securities. However, consistent sustainability argues in favor of investments in concentrated, individual and therefore mostly index-deviating actively managed portfolios. Active, though, is not meant in the sense of a lot of trading. In order to be able to exert influence by exercising voting rights and other forms of engagement, longer rather than shorter holding periods for investments make sense.

Still not enough consistently sustainable ETF offerings

When I started my own company in early 2016, it was probably the world’s first provider of a portfolio of the most consistently sustainable ETFs possible. But even the most sustainable ETFs were not sustainable enough for me. This was mainly due to insufficient exclusions and the almost exclusive use of aggregated best-in-class ESG ratings. However, I have high minimum requirements for E, S and G separately (see Glorious 7: Are they anti-social?). I am also not interested in the best-rated companies within sectors that are unattractive from a sustainability perspective (best-in-class). I want to invest in the best-performing stocks regardless of sector (best-in-universe). However, there are still no ETFs for such an approach. In addition, there are very few ETFs that use strict ESG criteria and also strive for SDG compatibility.

Even in the global Socially Responsible Investment Paris Aligned Benchmarks, which are particularly sustainable, there are still several hundred stocks from a large number of sectors and countries. In contrast, there are active global sustainable funds with just 30 stocks, which is potentially much more sustainable (see 30 stocks, if responsible, are all I need).

Issuers of sustainable ETFs often exercise sustainable voting rights and even engage, even if only to a small extent. However, most providers of active investments do no better (see e.g. 2023 Proxy Season Review – Minerva). Notably, index-following investments typically do not use the divestment impact channel because they want to replicate indices as directly as possible.

Sustainable investment and securities selection: fewer standard products and more individual mandates or direct indexing?

If there are no ETFs that are sustainable enough, you should look for actively managed funds, award sustainable mandates to asset managers or develop your own portfolios. However, actively managed concentrated funds with a strict ESG plus impact approach are still very rare. This also applies to asset managers who could implement such mandates. In addition, high minimum investments are often required for customized mandates. Individual sustainable portfolio developments, on the other hand, are becoming increasingly simple.

Numerous providers currently offer basic sustainability data for private investors at low cost or even free of charge. Financial technology developments such as discount (online) brokers, direct indexing and trading in fractional shares as well as voting tools help with the efficient and sustainable implementation of individual portfolios. However, the variety of investment opportunities and data qualities are not easy to analyze.

It would be ideal if investors could also take their own sustainability requirements into account on the basis of a curated universe of particularly sustainable securities and then have them automatically implemented and rebalanced in their portfolios (see Custom ESG Indexing Can Challenge Popularity Of ETFs (asiafinancial.com). In addition, they could use modern tools to exercise their voting rights according to their individual sustainability preferences. Sustainability engagement with the securities issuers can be carried out by the platform provider.

Risk management: much more tracking error and ESG risk monitoring?

For sustainable investments, sustainability metrics are added to traditional risk metrics. These are, for example, ESG ratings, emissions values, principal adverse indicators, do-no-significant-harm information, EU taxonomy compliance or, as in my case, SDG compliance and engagement success.

Sustainable investors have to decide how important the respective criteria are for them. I use sustainability criteria not only for reporting, but also for my rule-based risk management. This means that I sell securities if ESG or SDG requirements are no longer met (see Divestments: 49 bei 30 Aktien meines Artikel 9 Fonds).

The ESG ratings I use summarize environmental, social and governance risks. These risks are already important today and will become even more important in the future, as can be seen from greenwashing and reputational risks, for example. Therefore, they should not be missing from any risk management system. SDG compliance, on the other hand, is only relevant for investors who care about how sustainable the products and services of their investments are.

Voting rights and engagement have not usually been used for risk management up to now. However, this may change in the future. For example, I check whether I should sell shares if there is an inadequate response to my engagement. An inadequate engagement response from companies may indicate that companies are not listening to good suggestions and thus taking unnecessary risks that can be avoided through divestments.

Traditional investors often measure risk by the deviation from the target allocation or benchmark. If the deviation exceeds a predefined level, many portfolios have to be realigned closer to the benchmark. If you want to invest in a particularly sustainable way, you have to have higher rather than lower traditional benchmark deviations (tracking error) or you should do without tracking error figures altogether.

In theory, sustainable indices could be used as benchmarks for sustainable portfolios. However, as explained above, sustainability requirements can be very individual and, in my opinion, there are no strict enough sustainable standard benchmarks yet.

Sustainability can therefore lead to new risk indicators as well as calling old ones into question and thus also lead to significantly different risk management.

Summary and outlook: Much more individuality?

Individual sustainability requirements play a very important role in the allocation to investment segments, manager and fund selection, position selection and risk management. Strict sustainability can lead to greater differences between investment mandates and radical changes to traditional mandates: A lower asset class diversification, more illiquid investments for large investors, more project finance, more active rather than passive mandates, significantly higher concentration within investment segments and different risk management with additional metrics and significantly less benchmark orientation.

Some analysts believe that sustainable investment leads to higher risks, higher costs and lower returns. Others expect disproportionately high investments in sustainable investments in the future. This should lead to a better performance of such investments. My approach: I try to invest as sustainably as possible and I expect a normal market return in the medium term with lower risks compared to traditional investments.

First published in German on www.prof-soehnholz.com on Dec. 30th, 2023. Initial version translated by Deepl.com